Tom update: Tom’s recently had his second dose of chemotherapy which is given intravenously over the course of about four hours, after which he can go straight home. The symptoms from the first dose was limited to stomach cramps and a rather strong penchant for napping, and even these went away after about five days. A cousin-of-an-ex-of-an-old-school-friend-I-barely-talk-to-anymore who went through Hodgkin lymphoma told me chemo was “a bit like the worst hangover ever x10”, so it seems like there might be more in store for him. While the primary issue is the risk of infection (baaaddd news if he gets one…), his lumps have already gone down, which is amazing. 5.5 months to go!!

I always thought I’d be one of those people who would intensely research a disease which I was closely affected by, but this turns out not to be the case at all. Since Tom’s diagnosis over a month ago, I’ve been reluctant to learn more, perhaps for fear of what I might find.

When I did get round to looking up some of the questions I had, I found that there’s a dearth of mid-level info. It seems one has the option of A) the basic facts and stats from a multitude of cancer websites or B) scientific literature, not exactly known for its accessibility and readability. This post is my attempt at filling the gap between the two on the basic science of Hodgkin lymphoma.

Who was Hodgkin and what’s he got to do with anything?

Thomas Hodgkin was an English pathologist who was the first person to describe the disease now known as Hodgkin disease, or Hodgkin lymphoma. In 1832 he wrote a paper called On some Morbid Appearances of the Absorbent Glands and Spleen (I love old paper titles!), which begins with a very British self-depreciating introduction along the lines of “Err, I don’t think anyone’s going to read this, and those who are probably won’t find it new or interesting anyway”. After pulling himself together he describes his study of some cadavers that have very swollen glands in the neck, chest and groin but no sign of inflammation or other obvious disease which may have caused them. He offered very little in the way of speculation or discussion, and it wasn’t until 1865 that Dr Samuel Wilks resolved these symptoms into a single disease which he named after Hodgkin.

Thomas Hodgkin was an English pathologist who was the first person to describe the disease now known as Hodgkin disease, or Hodgkin lymphoma. In 1832 he wrote a paper called On some Morbid Appearances of the Absorbent Glands and Spleen (I love old paper titles!), which begins with a very British self-depreciating introduction along the lines of “Err, I don’t think anyone’s going to read this, and those who are probably won’t find it new or interesting anyway”. After pulling himself together he describes his study of some cadavers that have very swollen glands in the neck, chest and groin but no sign of inflammation or other obvious disease which may have caused them. He offered very little in the way of speculation or discussion, and it wasn’t until 1865 that Dr Samuel Wilks resolved these symptoms into a single disease which he named after Hodgkin.

Hodgkin’s paper here and a biography here

What’s the difference between a leukaemia and a lymphoma?

Leukaemia and lymphoma (of which Hodgkin’s is just one type) are both cancers of the circulatory (blood and lymph) system which is comprised of myriad cell types. Life as a blood or lymph cell is tough, and new ones must continuously be made to replace the casualties. The start of the production line is stem cells in the bone marrow which can take two different paths of differentiation. Some take the myeloid route and may finish up as red blood cells, platelets or many different types of white blood cell. Others take the lymphoid route which goes down the path to becoming infection-fighting T-cells and B-cells.

Note there are two main types of leukaemia. Myeloid leukaemia is caused by mutations early in the myeloid pathway and lymphoid leukaemia is caused by mutations in circulating cells early in the lymphoid pathway. Lymphoma however is a solid tumour caused by mutations further down the lymphoid pathway.

Because the myeloid stem cells differentiate into so many cell types including red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets, the symptoms of myeloid leukaemia can be quite severe including anaemia, immune deficiency and problems clotting.

The B-cells which mutate in lymphoma are normally found in lymph nodes distributed throughout the body, but the main ones are found on the neck chest and groin. It’s almost always in these areas where large painless lumps develop as the first symptom of lymphoma – so keep an eye on any if you have them!

For more information click here.

What’s going on inside someone with Hodgkin lymphoma?

This is the big question. The early characterisation and mercifully high survival rate of Hodgkin lymphoma doesn’t actually match up to how well understood the disease is at the moment (which is not very).

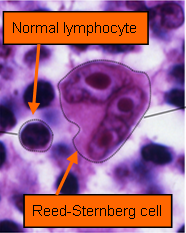

Whatever’s going on, it certainly has something to do with Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells, unusual cells which are sure signs of Hodgkin disease. There are dozens of other lymphomas which do not have RS cells, and these can be grouped together as non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

First noted around the turn of the 20th century, it wasn’t until about 15 years ago that genetic studies confirmed that they are a weird form of B-cell, a type of white blood cell which normally produce antibodies to fight infection. It took so long to figure this out because they look and act pretty much nothing like normal B-cells. Typically of tumour cells, they ignore chemical instructions from the best of the body, growing and dividing at their own rate and refusing to die when they’re supposed to. Despite this, RS cells only make up 1-10% of the tumour mass, the rest being assorted white blood cells and other cell types which cluster around it.

The changes which occur to turn normal B-cells into Reed-Sternberg cells are just beginning to be unravelled, but many of them are “the usual suspects” found in other cancer types. This just goes to show how important research into any cancer is, because understanding one form of the disease can greatly speed up research into others.

What are the chances and risk factors of getting Hodgkin lymphoma?

Around 1700 people are diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma every year in the UK. Hodgkin lymphoma is unusual in that there are two age groups which are most at risk – those aged 15-30 and those aged over 55. Men are slightly more likely to get the disease, and there does appear to be a genetic component but this is not well understood. There have been a number of suggested links to viruses like EBV and HIV, and other risk factors but none of these have been conclusively demonstrated.

How is Hodgkin lymphoma treated?

In most cases (including Tom’s), a set of four chemotherapeutic drugs collectively called ABVD are given intravenously every two weeks for 6-8 months. Using four different drugs rather than one is like going to battle with swordsmen, pikemen, archers and cavalry rather than hedging bets on just one type. Even if some cancer cells develop a resistance to one drug, chances are the other three will kill them off.

Each drug targets cancer cells in different ways:

Adriamycin (aka Doxorubicin) binds tightly to DNA, effectively tying the two strands together so they can’t split up to replicate.

Bleomycin causes breaks in DNA, killing off cancer cells which tend to have broken DNA repair machinery but merely slowing down healthy cells which have the capability to fix themselves.

Vinblastine stops cell replication by interfering with assembly of microtubules, important components of the internal cell structure and vital for separating chromosomes during cell division.

Dacarbazine add alkyl groups onto DNA which must be removed before correct replication can take place.

The reason chemotherapy drugs work is because they are most punishing on cells which are replicating quickly – and uncontrolled cell replication is a defining feature of cancer. This is good because it means that even though we don’t understand very much about Reed-Sternberg cells, we still have an effective strategy at killing them off. However there are other cells for which rapid replication is a normal and necessary feature, such as those of hair follicles and the gut lining. Killing off these cells is the reason for the two most common side effects of chemo: hair loss and nausea.

Side effects aside, AVBD has proved tremendously effective at treating Hodgkin lymphoma and the survival rate is one of the highest of all cancers, especially in the young.

Em x

———————

Great open access review paper on Hodgkin’s lymphoma: http://www.jci.org/articles/view/61245